Unexpected finds at the Vatican Museums: Fig leaf panties, a hidden drawer full of marble genitalia, and the pope’s graffiti artist.

Strolling through the galleries of the Vatican Museums in Rome you pass armies of ancient gods and heroes, frozen mid-step, mid-lunge, mid-song. Their pearly skin is smooth as the inside of a seashell. Their eyes arrest you. Their muscles ripple.

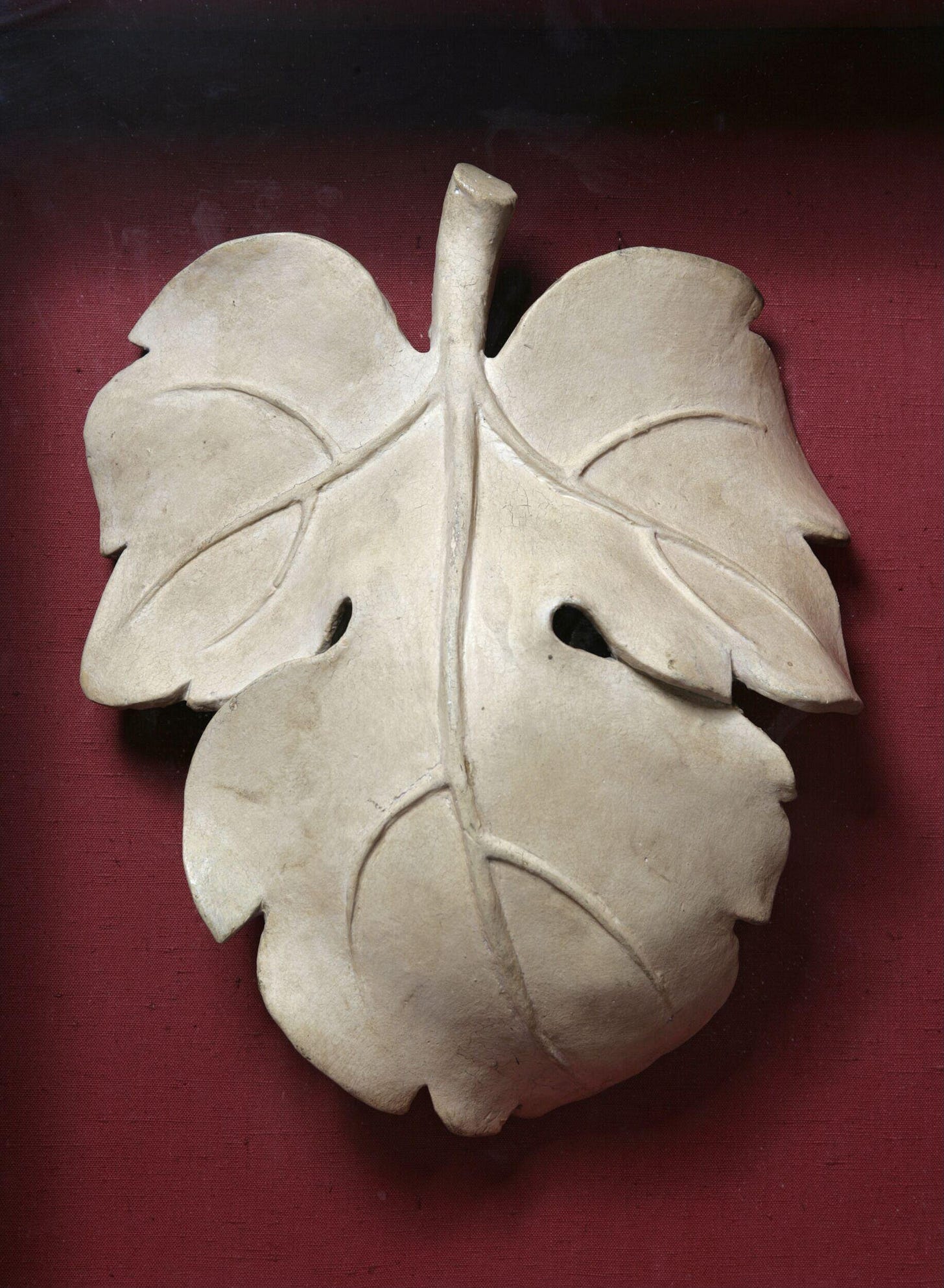

But there’s something wrong. Trailing your eyes down their marble bellies, you find…a fig leaf?

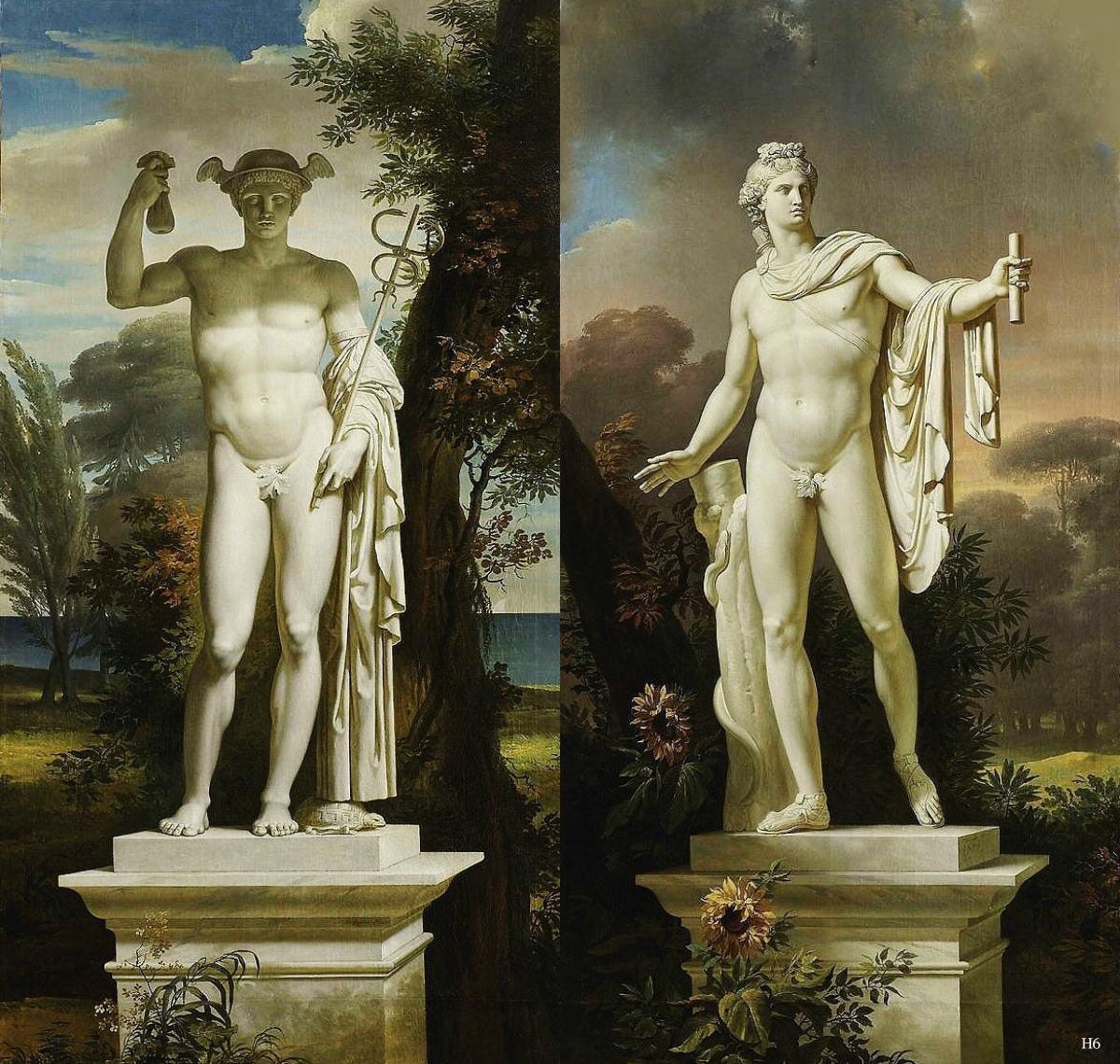

Many, if not most, of the Vatican’s collection of ancient Greek and Roman statues have been given fig leaf merkins to cover their characteristic nakedness.

On my first visit to Rome, these leaves shocked and irritated me. There is just something so wrong about them. The fig leaf’s sheepish modesty fits awkwardly on such regal, powerful figures. It just doesn’t make sense for Achilles to sheathe his sword, or for Dionysus to hide his grapes.

So who told them to cover up?

*Caveat: Most of this discussion will be focus on male figures in art. Male genitalia is just much more obvious than female. Most naked female figures in art bear a smooth mound, with no explicit genitalia visible. Harder to do this with the men, unless they had access to some duct tape.*

The Fig Leaf Campaign

The ancient Greeks loved to look at naked men (in art).

In ancient Greek art, male nudity represented virtue, strength, and harmony. Gods and heroes were nearly always unabashedly naked in painting and sculpture, and ancient gym bros exercised and competed in ritual games completely nude.

In the 15th century, Italian artists rediscovered the art of the Greeks (and the Romans, who themselves were inspired by the Greeks), and began to adopt their ancient style.

In the flurry of this visual revolution, Michelangelo sculpted his David. This statue is the perfect example of a core Renaissance thesis: to depict contemporary Christian figures in the style of ancient Greece. David, the biblical giant-slayer, stands in sublime contrapposto (posing with most of his weight on one leg). His startlingly lifelike body, with its solid strength and divine beauty, could just as well be dated to 400 BCE as to 1504 CE. But 16th century Italy was very far from the nude gymnasiums and pagan baths of classical Greece. As the story goes, when David was first unveiled in the Piazza della Signoria in Florence, the locals recoiled in disgust and began pelting him with stones. Soon after, he was gifted a couture skirt of 28 bronze fig leafs to conceal his offensive nudity.

In the time between the fall of Rome and Michelangelo, Christianity had come to dominate the western world. The heroic nudity of ancient Greece was forgotten. Now the naked human form symbolized sin, shame, and moral decay.

According to the Bible, Adam and Eve became ashamed of their nakedness after eating from the tree of knowledge, and sewed fig leaves together into loincloths to cover themselves (Book of Genesis, 3:7). According to Catholic teachings, sex was only “proper” when conducted for the purpose of procreation. Any pleasure derived from the act, or from the sight of a naked body, was a mark of moral impotence. In the art of this world, only the wicked went sans clothing.

Consider the above fresco by Luca Signorelli, painted at the same time that Michelangelo was chiseling away at David. Nakedness here has become abjection. Humans cower and writhe, lashed by demons in an eternal torment. This was how the Catholic Church wanted nudity to be portrayed: as a reminder of humanity’s original sin.

But Michelangelo disagreed, and in 1536 he came back for more. His fresco, The Last Judgment, covers the Sistine Chapel’s altar wall with a harrowing vision of the second coming of Christ and God’s final judgment of humankind. Conventionally, scenes of the Last Judgment “had been illustrated with figures clothed according to their social rank,”1 but Michelangelo decided to disrobe his Biblical subjects. The Church wasn’t happy. The pope’s Master of Ceremonies is reported to have said “it was most disgraceful that in so sacred a place there should have been depicted all those nude figures, exposing themselves so shamefully, and that it was no work for a papal chapel but rather for the public baths and taverns.”

The outrage surrounding this monumental work was a symptom of a greater disease: the Counter-Reformation. In response to Martin Luther’s calls for reform in the Catholic Church, the clergy rushed to stifle any signs of vice in their midst. This ascetic attitude spread to the art world, and in 1563 at the Council of Trent a decree was issued demanding that “all lasciviousness be avoided; in such wise that figures shall not be painted or adorned with a beauty exciting to lust.” And as a dig to their least favorite artist, the Council decreed also that “the pictures in the Apostolic Chapel should be covered over, and those in other churches should be destroyed, if they display anything that is obscene or clearly false.”

These decrees launched the “Fig Leaf Campaign,” the most comprehensive art censorship movement in history.

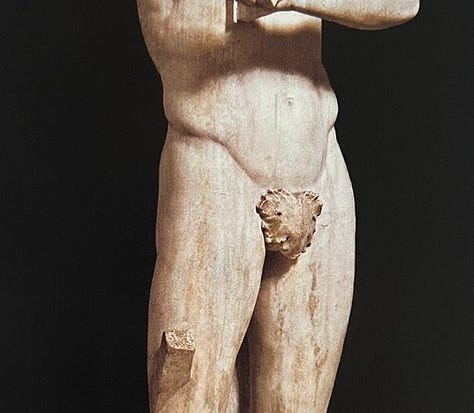

Thousands of sculptures and paintings, both contemporary and ancient, had their genitals smashed, ripped off, painted over, and covered with fig leaves. Rumor has it that there’s a secret drawer full of these castrated members somewhere in the Vatican.

Michelangelo’s death in 1564 meant that he wasn’t alive to see his masterpiece graffitied over by Mannerist painter Daniele de Volterra, who covered the figures’ genitalia with drapery on the pope’s instructions.

Rotten fruit

The majority of these censored works have not been restored. Plaster, marble, and concrete fig leaves hang off of countless precious sculptures like yellowed teeth. On a visual and aesthetic level, the obscuring fig leaves upset the harmony of the works they censor. The ancient Greeks and Romans sculpted their figures in contrapposto. This classical invention breaks the rigid symmetry of ancient Egyptian and archaic Greek sculpture, freeing up the human form. This imbalance lends the forms their essential life. It makes them appear real. The forced symmetry of the fig leaf, visually speaking, sits on top of this lifelike form like oil on water. It breaks up the fluid motion of the figure’s pose like a stone thrown in a runner’s path.

But what is most alarming about these fig leaves is that they completely fail to do their job!! It’s one of the most basic principles of psychology that “concealment breeds the desire to reveal”. Covering a forbidden thing only makes it more desirable. It calls attention to what is hidden.

What is more, the fig itself is rather an odd choice of weapon to beat the lust out of art. In ancient Greece, figs were symbols of fertility and abundance associated with Demeter, goddess of the harvest. They were also markers of physical virility, awarded to winners of athletic contests. In ancient Rome, the fig was associated with female genitalia, and viewed as a gift from Bacchus (Greek Dionysus), god of wine and inhibition. The interior of a fig resembles an “inverted womb,”2 while its external shape is decidedly scrotal.

The covering up of desire lowers it to a place of sublimation where the subconscious can romp freely. Shielding the image of a statue’s genitalia doesn’t make us blind and dumb, it sinks the imagined picture of those genitals down to the ocean floor where all our repressed desires lie like ravaged whale fall. The denial of pleasure raises the senses to a fever pitch of want. True eroticism lies in the tension of the unseen, the untouched, the untasted.

Thank you so much for reading!!!

This is such a rich topic with so so many examples that I would love to discuss more with you. If you have a favorite leafy nude please share!

(Also, if you’re interested in learning more about the Fig Leaf Campaign, the BBC made a great documentary.)

All love,

LoLo ❤️ 🍁

Why Fig Leaves Cover the Private Parts of Classical Sculptures, by Alexxa Gotthardt, 2018

Fig Leaf, Pudica, Nudity, and Other Revealing Concealments, by Seymour Howard, 1986

THIS! Is fascinating!!!!

Your posts are always such fun reads! Loved this