We need to talk about Achilles and Patroclus

Dialogues of desire from ancient Greece to today

“He is half of my soul, as the poets say.”

Why is it that a story first told more than two millennia ago is still the topic of academic debate, artistic obsession, and best-selling novels today? What is it about Achilles and Patroclus that fascinates us?

We tell their story again and again. We make them love, fight, die, and mourn — eternally. In speaking their story, we set them spinning on the revolutions of their fated destruction.

Like many people, I’ve been fascinated by the story of Achilles and Patroclus. The uncertainty of the truth of their relationship — were they lovers or just reeeaaaaallly close buds? — is intriguing. And the poignancy of a love between comrades at arms, on the pseudo-mythical stage of the Trojan War, will always sell paperbacks.

At first, I wanted to find out, once and for all: were they in L.O.V.E.?

But in pursuing this question, I came to realize that this isn’t about a question at all, at least not one with a shiny “yes or no” answer. It’s about a dialogue. A conversation.

The myth of Achilles and Patroclus, like all myths, is a tool we use to understand our current reality. We look to historical precedent to legitimize and elucidate our current experiences. That is why, today, so many members of the queer community are claiming the love story of Achilles and Patroclus. This historical example of homosexual love can be used to “validate identities that have been trivialised and dismissed" (

).1In reading the myth this way, we are re-contextualizing it to fit the framework of our modern belief in sexual identity. But rather than a misuse or misinterpretation of the text, this re-contextualization is the whole point. It is the active, fiery dialogue that gives the story its power. And this dialogue has been going on for thousands of years.

Homer starts the conversation

In The Iliad, Homer presents Achilles and Patroclus as a fiercely bonded pair with a deep emotional bond. It is very convincing to read this bond as inherently romantic, although Homer makes no explicit mention of it bearing any sexual component.

Achilles constantly refers to Patroclus as his “dear companion” and the two can often be found alone in Achilles’s tent. Patroclus is the only one who can rouse Achilles into action as the war stalls out, and he becomes visually married to Achilles by wearing his armor into battle. When Patroclus falls on the battlefield, Achilles lets “out a terrible scream” and falls to the ground, riven by grief.2 He refuses to wash until Patroclus is laid to rest. Later, Patroclus appears to Achilles as a ghost, unmoored between this life and the next, and begs him to bury their bones together in a shared grave. These are not the hallmarks of a platonic friendship.

The ancient Greeks talking: Aeschylus vs Plato

The ancients themselves couldn’t come to a consensus about the true nature of Achilles and Patroclus’s bond. They, like us, tried to understand the mythic relationship within the framework of their time.

In the fragments of the 5th-century BCE play by Aeschylus, Myrmidons, we see Achilles and Patroclus unambiguously in love. Achilles intones, “To me, because I love him, this is not loathsome,”3 as he stands before Patroclus’s corpse. The relationship is also painted as strongly sexual in the line: “And I honoured the intimacy of your thighs by bewailing you.”

In Plato’s The Symposium, Achilles and Patroclus are also explicitly named as lovers. However, the conversation turns personal when Plato refutes Aeschylus’s claims that “Achilles was Patroclus’s lover.”4

This is not a denial of the pair’s romantic relationship. Instead, it centers the discussion of the mythic couple firmly in Plato’s own time…

A crash course in bro-on-bro action in Classical Athens —

In the Athens of Plato and Aeschylus, erotic relationships between men were a crucial part of society. These relationships followed a common, asymmetrical structure. The lover, called the erastes, was an adult male (often in his 20’s), who played the active role in a relationship with a young male, called the eromenos, (often in his teens). Apart from satisfying physical desires, these relationships were meant to be pedagogical. The older, active male would teach the younger, passive male how to be a proper citizen. In this way, these same-sex relationships were considered noble and were enshrined in Athenian culture.

…So, when Plato says Achilles wasn’t Patroclus’s lover, he’s saying that Achilles wasn’t the active erastes, but was instead the passive eromenos, because of his youth relative to Patroclus.

Both Plato and Aeschylus use the myth of Achilles and Patroclus to support their contemporary social views. The practice of pederasty (referring to the relationship between an erastes and an eromenos) was becoming more widespread in Athens in Plato’s and Aeschylus’s time, so they re-contextualized the story of The Iliad’s “companions” to fit their cultural structure.

Medieval scribes talking

During the Middle Ages in Europe, the story of Achilles and Patroclus was thoroughly cleansed of its romantic depth. It was scrubbed clean by countless scribes and poets and left pale as a bloodless fish on a craggy shore. They, too, re-contextualized the myth to fit their worldview. To them, the Trojans were the heroes of The Iliad, not Achilles and his ranks of Greeks.

Achilles and Patroclus became the villains. This, along with the iron fist of Christianity, smothered all husky breaths of romance from the myth.

Paint talking: Dialogues on canvas in neoclassical art

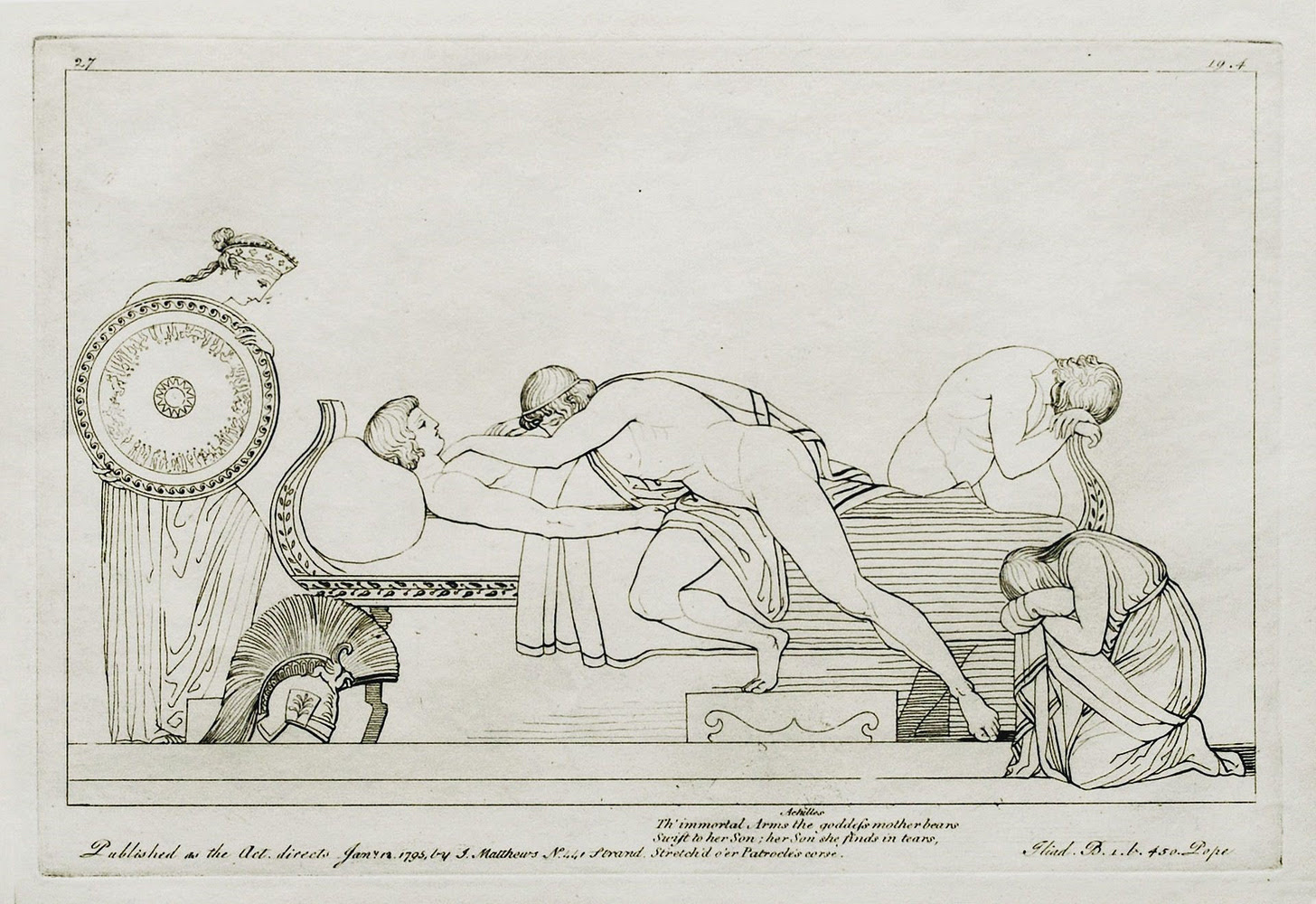

The story of Achilles and Patroclus would be caught in the wave of classical revitalization that swept Europe in the 18th and 19th centuries. As artists imbibed once again the fervor for ancient myths that had previously stimulated the Renaissance, Homer’s emotionally charged epics became the perfect subject.

History painter, Gavin Hamilton, here depicts the passionate grief of Achilles as he embraces Patroclus’s corpse. This scene draws from the intensely physical rituals of mourning Achilles performs in The Iliad —

“Putting his man-killing hands on the breast of his comrade and uttering ceaseless moans.”5

“Holding Patroclus in his arms, bitterly weeping.”6

While not explicitly romantic, this painting embodies Achilles’s grief: the tenderness with which he braces Patroclus’s limp head on his knee, the taught arch of his arm pulling his companion closer, his grief-stricken eyes piercing the heavens, begging the gods for relief.

Achilles keeps his men at a distance, as if to say “No, he is mine. None shall touch him but me.”

Nikolai Ge’s 1855 take on this scene is even more intimate. The figures are in a closed room rather than on the open battlefield. Patroclus’s body is laid on a bed, and a naked Achilles presses his flesh against the death linens. He shades his eyes, afraid to peer at the waxen face of his companion, but unable to look away.

Contrasting the almost regal portrayal of Achilles’s grief in Hamilton’s painting, Ge paints a deeply personal, quiet contemplation of grieving love.

Like the Classical Greek and Shakespearean literary references before, these paintings mold the Achilles/Patroclus myth into their artists’ contemporary cultural framework. The degrees of intimacy and romance can vary, but in both works, the relationship between Achilles and Patroclus is depicted at its most dramatic and emotional in order to display the artist’s grasp of Classical pathos.

The conversation continues…

Today, at least in Western society, we understand sexuality as a critical part of a person’s identity. This has incited a feverish desire to name what Achilles and Patroclus share. They are either platonic friends or gay lovers. Nothing in between.

In the 2004 film, Troy, with Brad Pitt as Achilles, Hollywood does what it does best — it sanitizes the myth, removing everything that made it wondrous and complex. There are no more jealous, bickering gods in this version. And don’t start to sweat over a lurking gay romance…Achilles and Patroclus are cousins!

Then, on the opposite spectrum, there is the soul-destroying book, The Song of Achilles, by Madeline Miller. This novel explores, from its inception, the romantic and sexual relationship between Achilles and Patroclus. It is a love story, plain and simple.

Our modern need to strictly codify Achilles and Patroclus’s relationship is blatant in these two examples. Today, when sexual proclivities define your very identity, there can be no room for ambiguity.

Thank you for reading!

If you want to read more about the ways art, literature, and history engage with love and human relationships, consider subscribing! <3

All love,

LoLo

Cosi’s Odyssey - Achilles and Patroclus

The Iliad, Book 18, line 30 (All references to the text of The Iliad refer to the 2011 Stephen Mitchell translation.)

Myrmidons, Attributed Fragments, from Loeb Classical Library

Plato, The Symposium, Penguin Classics edition, page 11

The Iliad, Book 18, lines 293-4

The Iliad, Book 19, lines 4-5

This was so interesting to read. I've always been fascinated by this story, and I understand the need to name what it was as you said. I think now we have this concept of the story, more romantic than centuries ago. Maybe because of the Madeline Miller book, maybe because of the importance it has to the LGBTQ community. It's so interesting to see the shift in the interpretation of the story throughout history tho

Its funny this article showed up while am in the last chapter of The silence of the girls…. I see her in every painting. Nonetheless I love how you explained the art depending on the time artist/writer lived in, gives a new scope to reading