A burnished tan face. Dark river stone eyes. Red lips pressed against a biting smile. And, of course, the unibrow.

This face, Frida Kahlo’s face, looks up at us from tables of mass-produced merch — mugs, t-shirts, notebooks — capitalism dressed up like feminism.

Her face has become ubiquitous. “Her image has morphed into a subdued, feminized, and whitened ideal of feminism for mass consumption that stands in direct opposition to both her life and artistic endeavors.”1 It’s easy enough to lift this lovely face from paintings like Self-Portrait with Monkey.

But it’s much harder to sell a tote bag with the Frida of My Nurse and I.

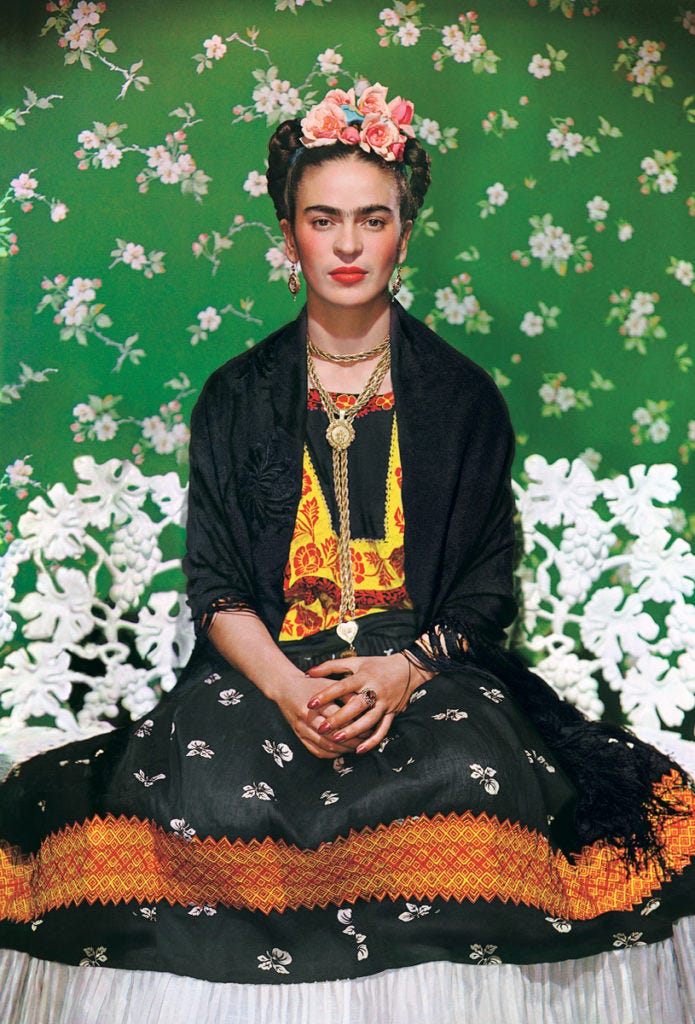

The irony of this commodification campaign is twofold. First, the vast majority of this Frida Kahlo merch is inspired not by her own paintings (nearly half of which are self-portraits), but by photographs taken of her. The most recognizable of which is the photo below, taken by her friend and sometime lover, Nickolas Muray.

Second, the easy-to-swallow Frida Kahlo that we’re served by the corporate overlords is unbelievably distant from the Real Kahlo. The Commodified Kahlo can be on your socks, your water bottle, even your unibrow sleep mask. The Real Kahlo’s art is disturbing, violent, gory, brutally sexual, and deeply psychological. The Commodified Kahlo is a passive object; the Real Kahlo makes herself the Active Subject.

When modern visual culture is dominated by images of Frida Kahlo that are not her own, images that are branded onto material objects for sale, this hard-won agency she forged for herself is blasphemed. We now know her not by her art, but by an image of her taken by someone else. We hear her story told in a voice that is not her own.

The Real Frida Kahlo

Let’s re-center the Real Frida Kahlo, shall we?

The resonance of Kahlo’s art comes from her ability to make the interior exterior. She accomplishes this by making herself — that is, her body — the subject of her paintings. This allows her to make psychological events luridly, putridly PHYSICAL. She explores internal events of love, pain, and creation through her own external body. This is the truth of her power, a truth that will never make it to the gift store shelves.

Part 1: Love

In her paintings, Frida explores her experience of love across the landscape of her own body.

Frida’s most infamous romantic partner was certainly her husband…then ex-husband…then husband again — Diego Rivera. Diego was one of the foremost muralists of the Mexican Renaissance. He met Frida while working on his first major commission, a mural for the National Preparatory School in Mexico City, where Frida was one of only 35 female students. The young Frida admired this older, successful painter who embodied the ideals of the Revolution. He soon became her mentor, and a few years later, when Frida was 22 and Diego was 43 (YIKES), they were married.

Thus begins one of the greatest accidents of Frida’s life (in her own words). Her relationship with Diego was volatile, emotionally abusive, and intensely erotic. She frequently cheated on Diego and was cheated on by him (once with her own sister!!). Frida once wrote that she wanted to “give birth to Diego Rivera. I am him. At every moment he is my child, my child born every moment, daily from my self." This dominating love is displayed in Diego On My Mind.

Here, Frida merges her face with Diego’s. Her forehead becomes a canvas within a canvas, bearing Diego’s image. This union of flesh makes literal the symbolic wedding vows she recently made (for the second time) with Diego. We can see how Frida experienced her love for Diego — overpowering, dominating, controlling, but also sensually connected. The painting is almost autoerotic: Frida loves Diego so much, thinks about him so much, that it starts to feel like she is loving herself, like she is becoming him.

But you can also read the work as placing the power within Frida’s body, rather than in Diego’s surveilling face. Here, he is her child, born “daily from my self.” He is small, petulant, and held just above her eyeline. It is Frida who dominates the frame. Her elaborate Tehuana outfit (notably a matriarchal culture) beams with light. Now, Diego starts to look like a fly caught in a choking spider’s web.

Love is a game of power, yes, but most of all it is a game of perspective.

Then there’s the Love of A Few Small Nips.

This work was finished in 1935, the same year that Diego had an affair with Cristina Kahlo, Frida’s sister. The title (also seen on the floating banner) refers to the words uttered by a man on trial for murdering his wife — “But all I did was give her a few small nips!” (crazyyy understatement). Here, the psychological pain of Diego’s many affairs is made physical. Each forbidden tryst is a weeping wound. The death blow to the heart must have been the joint betrayal of husband and sister.

Frida actually gouged the painting’s wooden frame and dappled it with drops of red paint, which she added to over the years she worked on the piece. This turns the painting into a matrix of pain, adding another meta-layer of ‘emotional torment turned physical violence’. It also brings the violence of the work into the spectator’s physical space, smudging the boundaries between internal (the world of the painting) and external (the world of the viewer).

Part 2: Pain

Every artist needs some flavor of traumatic back story, but Frida Kahlo’s is almost excessive. At the age of 18, Frida was riding a bus home from school when a trolley hurtled into it at full speed, crushing the bus against a street corner. Multiple people were killed instantly. Frida’s uterus was impaled by a metal handrail. She suffered multiple fractures to her ribs, collarbone, pelvis, spine, and leg.

This accident left Frida bedridden for months in a full body cast. For the rest of her life she would suffer debilitating pain, constant surgeries, and harrowing miscarriages.

In her paintings, Frida often explored her internal experience of this physical pain. Pain is, of course, physical. But most pain is invisible to the observer. The experience of pain is solitary, contained within the body of the afflicted. We can see a pulsing wound or a twisted spine, but we can’t SEE the experience of their pain.

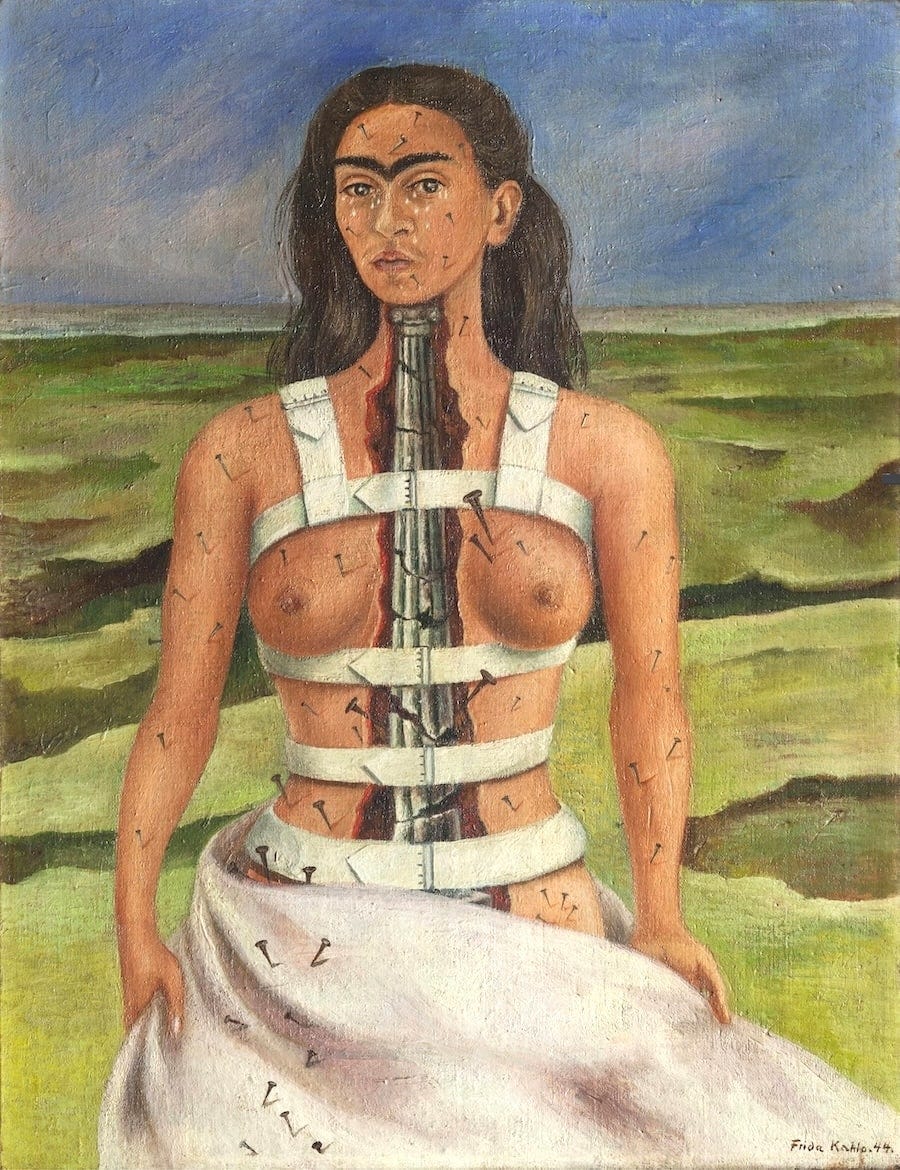

Frida brings her internal, psychological experience of pain to the external realm in The Broken Column.

Her pain is intensely psycho-physical in this work. Her torso is cleaved open, taking us inside her body to the locus of her pain: her spine. The Broken Column was painted shortly after Frida underwent spinal surgery, after which she was confined to her bed and strapped into torturous metal corsets (like the one pictured above).

Tears stream down her cheeks. Her gaze holds us, imploring us to see her, to feel her pain with her.

The isolation of her internal experience of pain is manifested in the solitary landscape she stands in. Her pain has even ruptured the earth, as craggy ravines and potholes lace through the soil behind her.

Her spine is an ancient Greek Ionic column, cracked and about to topple. Her pain is foundational, it reaches back across millennia to the ancient past. It rends not just the earth but the structures we have built upon it. In essence, her pain is the entire world, it is all of history.

Part 3: Creation

If Frida Kahlo’s work is about bringing the interior to the exterior, then My Birth is her magnum opus.

My Birth is the creation myth of Frida’s art.

A figure resembling Frida gives birth to the adult head of the artist. This is the thesis of Frida’s paintings — to create herself on the canvas: her body, her life, her pain, her love, all of it. Through painting, especially self-portraits, Frida gives birth to herself.

Like in The Broken Column, we see inside Frida’s body. Blood seeps onto the white sheets: the internal becomes external.

The act of birth, of creation, is quite literally an act of taking the interior to the exterior, of pushing the psychological, internal self out into the tangible, physical world.

Frida struggled in vain to have a child herself. So, in many ways, her art became her surrogate child. The countless “Fridas” she painted became her daughters. You can almost imagine her sitting, surrounded by her children and her children’s children, all with the same face.

Thank you SO much for reading! I truly can’t fathom how there are over 2,000 of you now! THANK YOU THANK YOU THANK YOU for being here!!

All love,

LoLo ❤️

Commodifying Icons: The Commercialization of Frida Kahlo, by Priya Prasad

love love this!! never sits right with me how all frida khalo merch is the same photo of her, diminishing her to a figurehead as opposed to spreading her art, a very common theme with women artists…

I enjoyed every word ffom this article! This is literally my favorite way of interpreting art❤️